By Professor Michael Widener, Department of Geography & Planning, University of Toronto

It’s happened to many of us. You’re running around the city, preoccupied with the many tasks that have to get done – pick up the kids, swing by the bank, check in with work. In an all too brief moment of quiet, you hear your stomach rumble and remember you forgot to eat lunch! Across the street you see a fast food restaurant, and decide to swing by for a quick bite before you head off to the next event on your list.

This feeling of being rushed is common, and it affects how we interact with the world around us. Time pressure, as it is often called, is a type of stress we experience when we feel like we don’t have enough (real or perceived) time to get everything done. To cope, we change our behaviours to help free up valuable time. At the Spatial Analysis of Urban Systems Lab at University of Toronto’s Department of Geography and Planning, my graduate students and I are exploring how time pressure affects when and where we shop for and eat food.

In the not so distant past, the “food desert” concept was commonly used to understand who had access to healthy and affordable food options. Food deserts were usually defined as regions of cities where residents lived beyond some distance from supermarkets and grocery stores. These residents were hypothesized to be at a disadvantage when it came to maintaining a nutritious diet, and were subsequently at risk of a wide range of chronic disease (e.g. obesity, diabetes, cardiovascular disease).

However, food deserts tend to oversimplify the relationship between urban residents’ locations and where they got their food. Thinking only about geographic access, in a city like Toronto, there is no shortage of food retailers and restaurants to choose from, especially for those who live nearby a subway station or have a car. So in this context, when evaluating who has access to healthy food, it is critical to think about other important factors, like a resident’s income, family size, daily activity pattern, the cultural appropriateness of food, and time available to cook and clean.

My team is currently using a range of datasets – from Statistics Canada’s General Social Survey’s Time Use questionnaires to GPS and food purchasing data collected in the recent Canada Food Survey – to explore how time use and pressure influences the types of food we buy, and where we buy that food. We are also working on designing research projects that will allow us to capture how this all eventually leads to better or worse long-term health outcomes, and what types of policy interventions can be designed to improve access to and consumption of healthy and affordable foods. We were also recently awarded a 4-year $222,016 SSHRC Insight Grant in the spring of 2017 that will allow us to collect data on these issues locally using GPS tracking and activity diaries. Ultimately, the analyses that result from these projects will help us design policy interventions to improve access to and consumption of healthy and affordable foods.

At the end of the day, we know we probably aren’t going to make people less busy. But, we hope to change urban food environments so that it is a little easier for the person on the run to have a nutritious meal as they dash to their next errand.

This work is being funded by the Connaught New Researcher Award ($20,200), Toronto Public Health ($15,864.60), and a subaward from the Canada Food Survey ($2,200), and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council ($222,016).

Relevant Links

Department Link: http://geography.utoronto.ca

Personal Webpage: http://www.thinkingspatial.com

Lab Webpage: http://www.sausy.ca

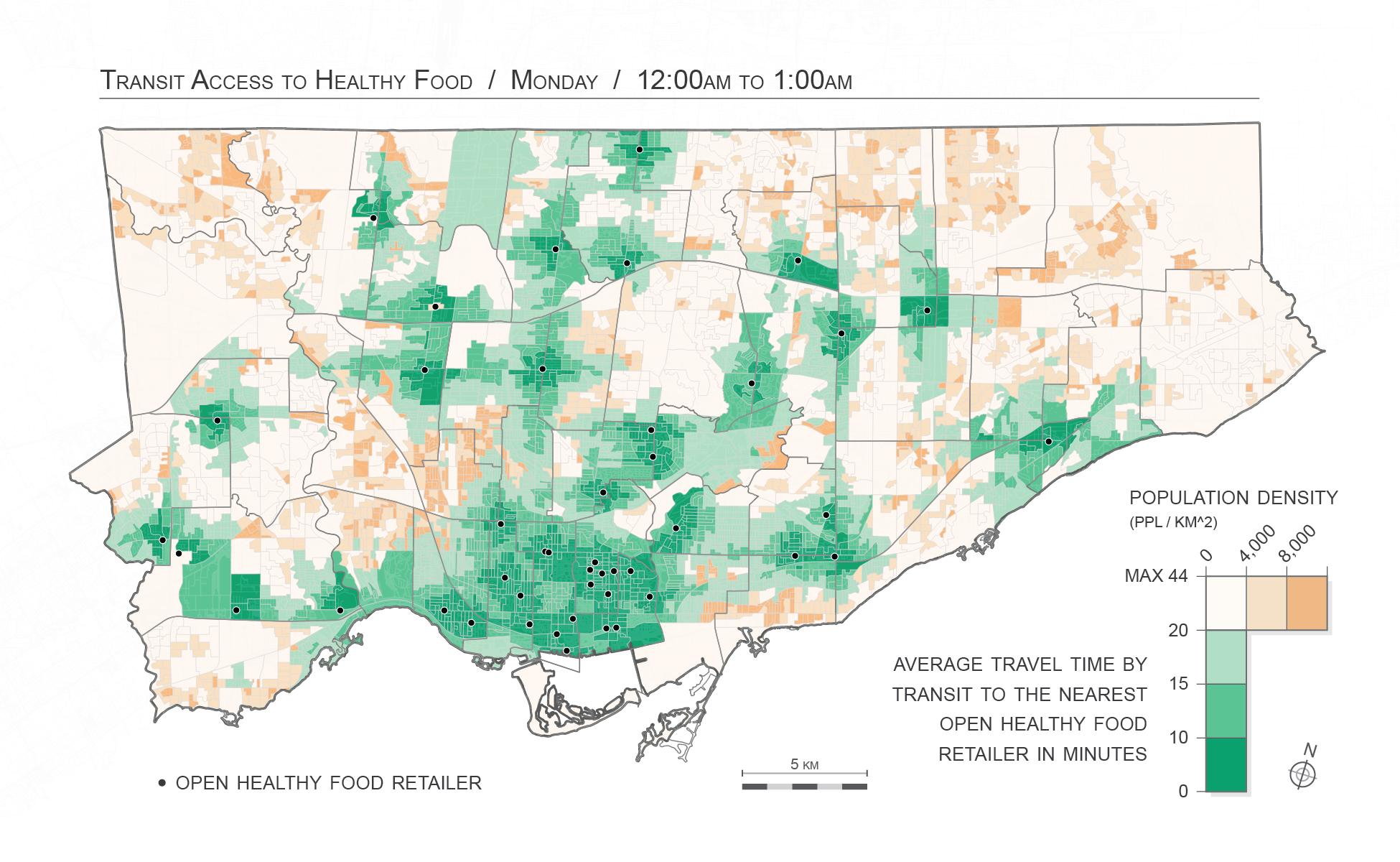

Distribution of total travel time to and from a grocery store or supermarket by transportation mode for Canadians living in an urban region (CMA).